Post-Empiricism as the Anti-Fragile Assessment Psychology

I’m going to make a longer post with a table that includes recent publications, shoutouts to student coauthors, and the theoretical implication for each of these papers – organized across domains of thought that I think are important to advancing personality science. I’ve used this blog a few times now as a way to notetake my thoughts as I go throughout the process of publications etc. In doing so, it has helped me organize my philosophy of science and come to understand better what it is in relation to the field. Largely, I find myself to identify with the term “post-empiricist” to best describe my critical, intersectional, and (at times) anti-empirical reliance on objectivity and control. I have put these thoughts together in a paper that I have submitted for publication, but I have shared with a few trusted folks already to get feedback and reactions. I thought I might share it here as well, in it’s unpublished form. I’m uploading it to a public pre-print server later today as well and will add that information below.

methods thoughts

We must move beyond traditional statistical and research-based approaches to focus on item experience—the process by which individuals attend to, interpret, abstract, and respond to the constituent elements of a test item. Each of these elements—wording, implied time frame, reference class, emotional salience, response format, and contextual assumptions—contributes to an item-level environment that shapes how the item is experienced rather than merely endorsed. It is this item-level environment, interacting with the contextualized individual, that produces the observed response. Subgroup analyses attempt to model relatively homogeneous patterns of these item experiences, with the recognition that any subgroup reflects structured regularities rather than uniformity, and that similarities and divergences exist both within and across groups. This complex experience of item experience is the abstraction process, so it seems to me (if by nothing but by another name). I do not believe we can explain this process to the point of actuarial supportial in our tests for their specific items in their current form, and this poses a substantial problem for the field and the practice of assessment. That, itself, is where bias is found (or may be) and decades of evidence suggests it’s there. I dont think we have this type of data for any test, and given the politicicalization of the judicial, extreme caution to protect minoritized communities becomes even more paramount. This gap of knowlesge is a major problem needing a complex solution fast, or not merely risk real harm but nearly guarantee more of it.

Symptom Validity

I’ll be posting an update soon with a number of papers and such from the last year, along with links to those PDFs and a brief discussion of what I found in each and how I think about it. I wanted to make a few notes about SVTs and symptom validity testing here, and how I’m seeing the literature broadly. It seems fairly clear to me that there are not reliably and incrementally useful differences in the supposed domains of over-reporting (e.g., cognitive, psychological, somatic) and that things, instead, seem to function in a more unified manner – with over-reporting as a general function.

My way of thinking about this currently is that as abstraction processes loosen, as a function of controlled executive function, mood regulation, or other cognitive process – intentionally [consciously] or not, the greater the interpretive band about item meaning becomes. As it loosens, I expect that people try to apply novel ideas to bounded language concepts – leading to poor description (such as when trying to feign psychosis, e.g., dissimulation) or other inaccuracy of type (misunderstanding normal or symptom trajectories). I think this is why we are seeing the same patterns repeat across MMPI-2/RF/3 and PAI+ over-reporting scales. Its why the same moderators appear, and why effect size ranges tend to standardize. I think scores outside of this range are likely an unrealistic example of abstraction processes – its also why they most often occur in simulation designs with students, the weakest feigning/malingering/etc design. It seems like what is happening is that there is a general bounded ceiling to which most people adhere (with, of course, deviations from bounding) – similar to how without speed limits everyone has a speed they feel ‘most comfortable with’ while driving. There are speed demons too, of course.

I was looking at some of the ratios of change between conditions/moderators across meta-analyses (Herring et al., Ingram & Ternes, Sharf et al., etc etc.) and it seems like the ratio between the domains decreases as the hedge’s g/cohen’s d of the overall effect size increase. This reinforces my belief that its a bounded system driven by this more cohesive and unified over-reporting process.

I’ll be posting some of the articles that focus on this in detail that published this last year shortly, and will have several updates about papers upcoming that tend to point to the same findings, including national VA samples with the MMPI-2-RF

modeling and measurement

I’ve been thinking a lot about behavioral modeling, particularly as it relates to validation of non concurrent prediction. In psychological reorganization (beh change), within-person variability is likely to increase, particularly when constraints are loosening (eg social or environment expectations and personal rules/strategies) and alternative (competing?) response strategies are active, dynamic and conditional indicators emerges. As systems change, other change occurs and thus change produces change and variability is a probable, bayes indicator of risk (eg HRV).

Change is increasingly likely when paired with a goal directed response strategies with more task demand, greater incentives, and cognitive factors (load, insight, etc) offering a strategically constrained process of change. These features permit interpretation of personality and validity processes as dynamic systems rather than fixed trait expressions. work on personality functioning and variability highlight one element of this pattern to me, though focused on trait theory tied to PD which, while a core element, likely forgos other transdiagnostic constructs and processes. I suspect that repeated measure approaches, for this reason, offer better predictive modeling, following basic QFT model patterns and building on more stable forces (eg trait) as predictive behavior modeling. It reminds me of an implication of Chris Hopwoods work (see below link) and AMPD more broadly

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00223891.2024.2345880

All problems are measurement problems. svt seem to function in a standard range of effects, differentiated by method of measurement (eg mean difference is .7 to 1.3, sens/spec via Larabee limit, etc). These effects are likely part of the stable field functional analysis. Im increasingly confident in the vitality of the SD and standard effect ranges in understanding individual prediction, rather than group focused models which dominate Psychology and assessment moreover.

Disruption proceeds change.

Art Trail

Over the last year, I’ve been working with HDFS Faculty Dr. Jackson in collaboration with The Louise Hopkins Underwood Center for the Arts (LHUCA) to strengthen Lubbock’s First Friday Art Trail. This project started during my time in the provost’s office working on outreach and engagement, with my primary role being to generate societal impact survey data. Over the past year we’ve been piloting a variety of questions and building relationships around the community (TTU and otherwise). This fall marks the first (soft launch) data collection for the 2025-2026 year. The survey’s data is being analyzed to generate tourism data used to justify city funding (e.g., where people are visiting from, where they stay while visiting via hotel tax) and generate community-driven directions for growth. One area that I’m excited to begin working on this fall is the creation of an App for the FFAT so that visitors (new and repeat alike) have an guide at their finger tips, with searchable vendors, event timelines, and more. The team (which includes vendors) is so excited.

Research Update

I wanted to provide an update on several exciting projects. There are a ton of excellent ongoing projects that will be included in future updates, but here is a summary of some recent papers.

Recently Published

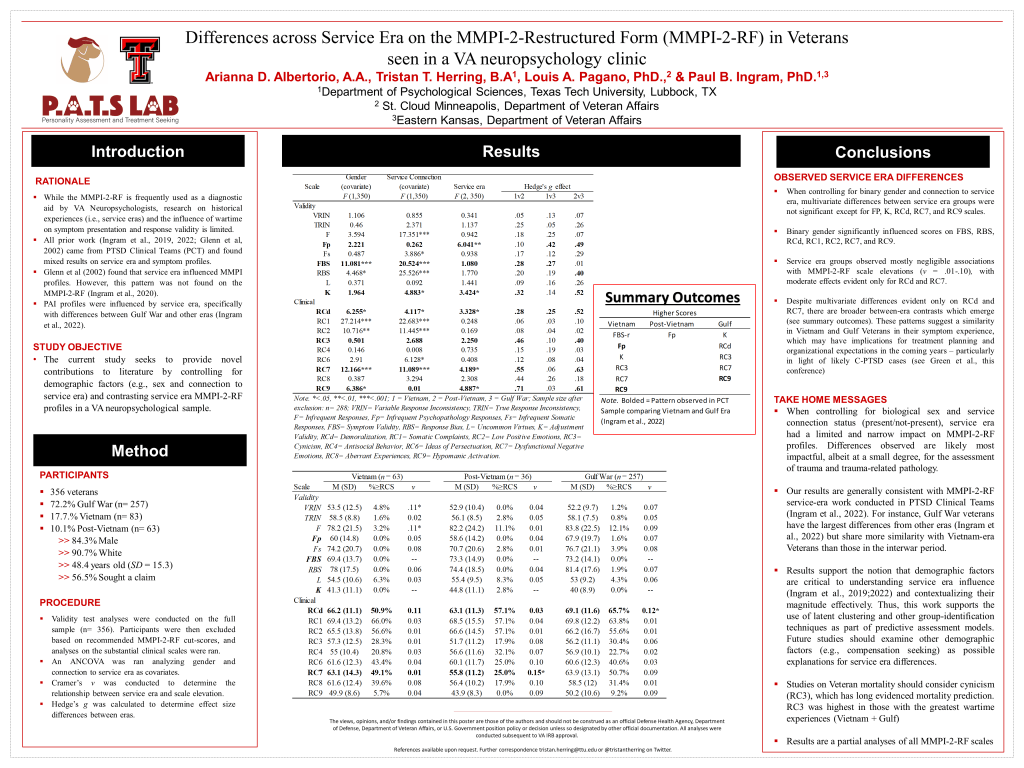

- Keegan has done some great work expanding contextual interpretation of the MMPI-2-RF in the VA. He took a look at the influence of service era in a neuropsychological clinic on the MMPI-2-RF, the first such examination outside of a PTSD clinic (in press). Consistent with past research he found less pronounced differences between combat era veterans (e.g., Vietnam/Gulf) compared to non-combat era Veterans (see also Ingram et al). In another paper, he took a took a look at the influence of undergoing a C&P evaluation on scale scores. Both are in press at Psychological Services.

- Tristan’s meta-analysis of the PAI is out in Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment (Great work also Keegan!), available here. It establishes an updated level of expectation for validity scales on the PAI, typically falling between the .7 to 1.3 range with typical moderators (e.g., setting, simulation, etc.). His first, first author.

- My work with Robert Shura, Pat Armistead-Jehle, and Ryan Schroeder on the nation wide assessment project is ongoing. The PAI National Sample focused on validity scales is out now in Psychological Assessment, available here. This resource should help clinicians incorporate base rates into validity decisions for SVT, a critical consideration particularly given limitations in SVT function.

In order to provide more regular future updates, Tina is going to be helping me! 🙂

Symptom Validity: Some observations and Comments about Over-Reporting

In my view, many of the most important and most interesting questions we have about symptom validity remains either unanswered, or rarely explored. The purpose of this paper is to outline some patterns I have observed, and to describe what I believe are critical steps for the future of the field – and for the development of the scientific practice of validity interpretation more specifically.

- Feigning detection typically within a standardized band of effect, regardless of instrument used, condition, and even study type in most cases. These effects differ according to the specific statistical analysis.

a. Mean effect differences typically range between .70 and 1.30, with a standard deviation approximately half of the mean effect

b. Sensitivity ranges from .10 to .50 with an average of .30, with specificity set to .90. This standardized effect range has been termed the Larabee limit” by some.

c. Correlations between SVTs are high, often falling within a large effect range. These between domain correlations appear robust, and do not appear to differ much between distinct symptom domains of over-reporting (e.g., somatic, cognitive, and psychopathology)

i. These associations will typically be between r = .75 and .85

ii. Differences are typically around a small effect (r~|.10|) - Moderation patterns are generally typical across instruments, and have not changed as a function of the development of new instrument versions (e.g., transition from the MMPI-2 to the MMPI-2-RF, or MMPI-2-RF to MMPI-3). This pattern is consistent with assessment instrument developmental broadly [e.g., portion of cognitive test changes between WAIS/WISC versions have similarly declined in time. For instance, the purpose of an evaluation, the type of client, their diagnosis, are their racial and ethnic background are each major and common moderators of effect. Moderation tends to be a question only of meta-analysis, which tend to reaffirm these patterns such that they can be acknowledge but not explored in follow-up study.

a. Moderation patterns are rarely explored in experimental (simulation) designs, which is a missed opportunity to advance understanding of how, when, and why people respond in the manner that they do.

b. Meta-analysis evaluating criterion variables (e.g., PVT and SVT used to create criterion groups) is limited, and not possible because of how these groups are created in the literature (See Herring et al., in press – PAI Meta). - Participatory research is rare in feigning research on personality assessment, leading to a potential for over-interpretation based on assumptions. In general, it is my perspective that the study method approaches used in the development of self-report assessment often serve to reify the ideas measured based on face validity, from the perspective of the test developer. Such approaches are similarly common on substantive scales, which is why recent work has suggested the scales are not viewed in the same pathological way in a variety of groups (e.g., MMPI-3’s RC6/RC8/CMP scales).

- Most individuals who are identified as over-reporting during research studies (e.g., Known-Group Designs) score below the recommended cutoff scores for scales. Thus, positive predictive power is often low for scales, indicating that it is common for them to go undetected and highlighting some of the concerns raised by Leonhard’s thoughtful papers from 2024.

- In research, the following are not typical but seem useful to developing and advancing our theory and practice of over-reporting detection. As such, we do not have a clear consensus of what effect requirements to support more clear and concise measurement, and thoughtful discussion and debate is needed to set benchmarks for when and how to answer specific interpretive questions. Advancing methods is a key want to improve this discussion. I sometimes describe this process as one in which assessment psychologists have used face validity to reify theory, rather than taking the next step and testing assumptive processes, including:

a. SEM models to test moderation and multivariate patterns.

b. Additional group analysis inclusive of each PVT/SVT criterion, providing fruit for long term Meta-analytic interpretation.

c. Correlations Matrix of between scale relationship

d. Comparison of individual scale effects and determination of incremental utility

e. Consideration of elevation patterns following configural approaches (e.g., awareness of their multivariate nature as a lens through which meaningful interpretation is possible).

Updates (some of the many)

So many things, so so many things (hopefully I didn’t miss too many big things)

Our paper on the MMPI-2-RF/3 Scale of Scales (SOS) development is out in JCEN (in press now, as of today), producing a scale that uses a symptom severity approach via the RC scales for broad and effective over-reporting detection. The scale adds to existing scales and performs well in both simulation (Morris et al., 2021 data) and clinical (Ingram et al., 2019 Active Duty) datasets. Great work Tina, Cole, and Megan. A PDF of the paper is linked HERE.

- A paper evaluating telehealth equality to F2F assessment using the MMPI-2-RF/3 was also published in JCEN’s special issue on validity testing development. This study used a sample of Veterans (via Robert Shura collaboration) undergoing ADHD evals. Results suggest equivalence of scale performance, consistent with prior simulation studies (Agarwal et al., 2023). Great work Ali! PDF of the paper HERE!

- The SUI scale is a leading measure of risk within the MMPI, and it was expanded and revised during the MMPI-3 release. In the first study to examine the SUI scale’s longitudinal associations with suicidality, Cole published a paper in the Journal of Clinical Psychology (JCP) examining its predictive (6-week, 4 data points) utility. A PDF of the paper (proof, pre-release and not official) is HERE! Chloe, a former undergrad, is also on the paper! Nice work Cole and Megan.

- Megan recently had a paper accepted into the Journal of Personality Assessment which evaluated the utility and interpretation of the ARX scale of the MMPI-3, given its revisions. The study uses two samples (PCL-5 and CAPS) for separate screening and diagnostic interview criterion. Results suggest (1) PCL and CAPS outcomes are highly related, consistent with past work, (2) cut scores for ARX are likely to aide in screening for potential traumatic events, (3) some domains of PTSD are more associated with ARX elevations, which may require additional administered scales to fully capture pathology related to trauma. Great work Megan, Cole, and Tina. Tina lead the CAPS sample study, which was their McNairs Thesis!!! Get the PDF HERE

- Luke won another poster competition (no fun picture, I’m sure he’s sad)- this time at the first annual Division 12 (Clinical Psychology) Midwinter conference. His work is looking at PTSD assessment in AD personnel via the MMPI-2 and MMPI-2-RF, expanding on what was presented at the Combat PTSD conference (look at his award picture!) and related to his 2024 SPA poster on the MMPI-2-RF scores. Although Pk added incrementally to AXY in the prediction of clinician diagnoses, with appropriate cut scores neither scale outperformed the other in terms of diagnostic decision making and clinical utility. These results support recent work establishing how the ARX/AXY scale can be used as a diagnostic aide (Keen et al., 2023), but it is critical to recall that scale elevations alone are not diagnostic.

- Student athlete work is ongoing with the MMPI-3, and two papers presented at the 2023 SPA conference are in works. The first evaluates the CMP scale using a mixed method approach, with qualitative coding suggesting poor utility and high elevation rates in athletes unrelated to pathology. The second provides a comparison sample with therapy engagement prediction, suggesting that select internalizing are some of the best predicts. Kacey from Kent State is helping lead the writeup on some of these, along with Sarah, Megan, and others. This work ties in with Pearson’s recent addition of student athlete comparison groups for the MMPI-3.

- There are also the TONS of upcoming SPA talks and posters, including a new meta-analysis of the PAI (Tristan), applications of IRT to Likert scale items on OR scales with the PAI (Keegan), under-reporting in Veterans (Keen), trends in training on assessment within the VA (Ali), over-reporting detection with pro-rated MMPI-3 scores (Me, Pat, Yossi, and Bill), and more. Megan also is presenting some over-reporting study information for the MMPI-A-RF, with one of our AMAZING undergrads first authoring a paper. A collab with Dr. B and her student Efrain is also looking at over-reporting on the MMPI-2-RF (Morris data, which was administered via the MMPI-2-RF-EX). I’ll give updates on all of those studies after the conference with materials.

Contextual Considerations: Service Era

Here is the first of the dives into posters presented this year at the Combat PTSD conference. Great work by Tristan and Ari on this one!

There is a history of research looking at the influence of Service Era on broadband personality assessment inventory instruments (Glenn et al., 2022 [MMPI-2]; Ingram et al., 2020a[MMPI-2-RF]; Ingram et al., 2021 [PAI]). All of this work has been conducted in a PTSD Clinical Team (PCT) and has found that, except for the MMPI-2-RF, there is notable influence by service era that warrants unique clinical interpretations – even after controlling for things like combat exposure and gender. This new research presented at the 2023 Combat PTSD Conference in San Antonio expands the existing literature in a few ways:

- It offers the first examination of Service Era outside of PCTs, providing a test of generalizability of the MMPI-2-RF’s lack of influence by service Era.

- It provides the first evaluation of service era influence after controlling for service connection status.

- It helps contextualize a new VA clinic sample that has not yet been evaluated as part of nation-wide datapulls (see Ingram et al., 2019; 2020a, b; 2022 – each year links to a different paper from that research project)

The results are great news. Prior service era findings for the MMPI-2-RF (i.e., that it didn’t influence scale scores beyond other demographic data) were supported. It looks like good news for less biased assessment methods for the VA when using the RF. One thing that is important to note is that the significance of the covariates seems to follow a general pattern of endorsement consistent with internalizing pathology mainly. As we continue this work and evaluate the remaining substantive scales it will be interesting to see if those patterns emerge consistent with trauma-pathology – a notable possibility in my view of the literature of VA assessment trends.

Next time I have a few I’ll write about PTSD screening with the MMPI-2 Clinical Scales and Restructured Scales (Luke’s Poster, student poster award winner!)

Back from the 2023 Combat PTSD Conference

Man, we had a blast. First off, Congrats to Luke Childers for winning a student poster award for his research looking at PTSD diagnosis in Active-Duty Personnel Using the MMPI-2. Killed it. Also, everyone did some awesome research – we had stuff looking at PTSD screening in two separate samples (AD and Veteran), we had a paper looking at the MMPI-2-RF validity scale patterns of elevation in a compensation seeking sample undergoing neuropsychological evaluation, and finally, a look at service era’s influence on test performance on the MMPI-2-RF in VA disability evaluations. I’ll write about each of these studies separately in short order, but til then – have some pictures of the fun!